Until quite recently my exploration in the Peak District had been solely on the southern and central regions, largely to keep the journeys down to an hour or less for day trips. The only visits north of Edale were to climb Kinder Scout, the tallest of the park’s peaks. It was not until recently that a friend mentioned the wreck of a US Airforce B29 Super Fortress that had crashed in 1948 whose remains were still visible on Bleaklow. We decided that we would set off to Snakes Pass the following week to see it for ourselves.

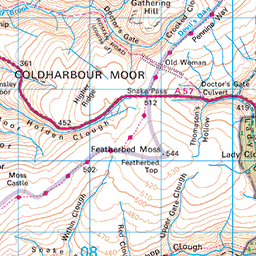

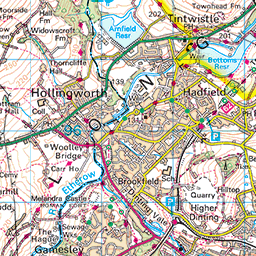

I came across Snakes Pass by chance while exploring the OS maps and in the previous year went on a couple of walks to explore the area. The approach to the pass from the south crosses a bridge at Ladybower reservoir where, heading east you approach a microcosm that is unlike other parts of the Peak District. You learn to expect certain things from the Peaks: Craggy edges, Heather covered moorlands and small stone villages surrounded by arable land. Instead, Snake’s pass is a dense, slightly claustrophobic road that passes under steepening hill sides and pine forests that feel like the frontiers of North America.

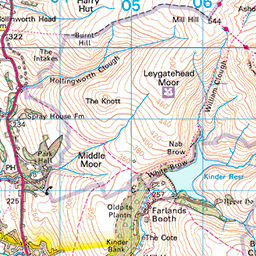

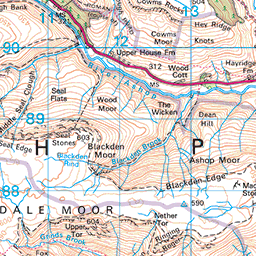

The typical route to the Bleaklow Bomber involves parking at the layby where the Pennine Way crosses snake road and walking a short distance north to the Higher Shelf Stones, before veering south again to find the wreck. We opted for a slightly more secluded and longer route because we wanted to avoid crowds and see a bit more of the bleakness of Bleaklow.

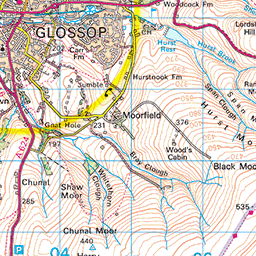

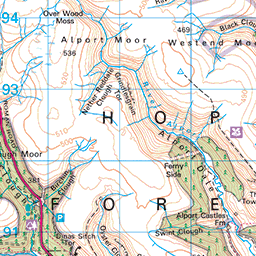

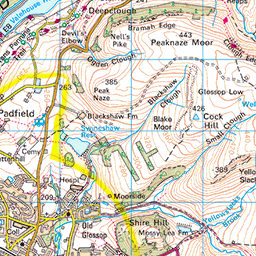

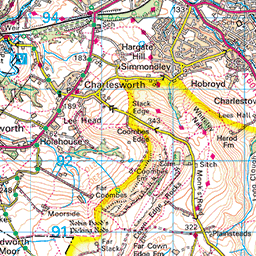

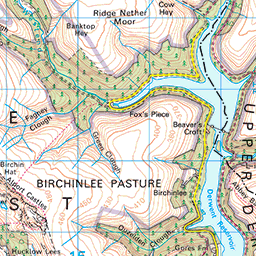

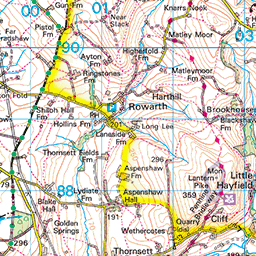

We parked at the Forestry Commission car park in Birchin Clough. There is an obvious gate in the carpark that begins a steep 100m climb up north towards the moors above. It is a tough start, but it certainly warms you up quickly on a cold day. The footpath marked on the OS maps abruptly ends as you ascend above the pine forest but there is a visible, if broken, path that follows due north.

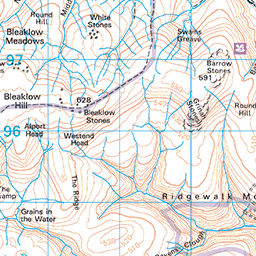

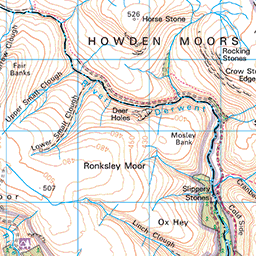

Heading due north for approximately 3km we meet the steep edges of the River Alport. Continuing north we followed the river to a flat dip in the land forebodingly called “The Swamp”. The Swamp separated us from the Pennine way and whilst quite wet we were easily able to navigate across thick sections of grass that created stable footing to avoid the soggiest patches of ground. In areas that were impassable we simply reroute to the high ground.

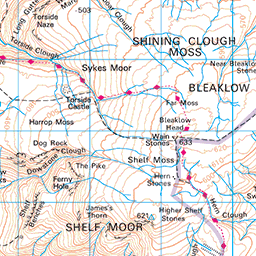

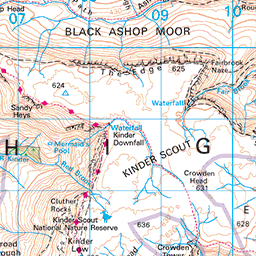

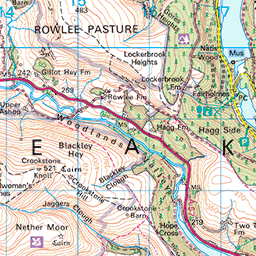

Having crossed the worst of the swamp we ascended a short hill and joined the very well-trodden Pennine Way. The Pennine way is England’s premier long-distance footpath, stretching 412km north from Edale to Kirk Yetholm. We would only be joining it for a short time, heading north west until the Higher Shelf Stones were visible. We cut across south to the stones to stop for some lunch.

From the stones it is a 500m traipse across boggy, unmarked land to get to the crash site. We had been blessed with clear weather, so it was easy to find. On a day with poor visibility the navigation would be considerably more difficult.

The crash site is part monument, part museum. There is a small shrine to those that lost their life and a bronze plaque marking the incident. Strewn across a 500m area are pieces of scrap metal and rubber that, one assumes, either too cumbersome, or not interesting enough to have bene looted over the preceding 70 years. Large sheets of metal that formed up the wing and fuselage are identifiable. The landing gear and engine blocks the most recognisable parts. We spend a lot of time walking up and down trying to piece together the form of the plane and to grasp a sense of the scale of the crash.

As we explore, a thick fog rolled in and reduced visibility to less than 5 metres. The accounts of the crash suggest that the pilot, flying ‘by instrument’ because of the lack of modern navigation technology, had misjudged the distance they had travelled and began the descent into thick fog too early. They had likely crashed before they saw the ground and it became immediately apparent how this was possible as the weather rolled in.

It started to snow so we walked back to the Pennine way and headed south to meet snake road. Our plan had been to follow a footpath along the snake road and into the woods. We could not find an obvious way down to the path immediately so followed the road for some distance. There is a raised pavement that is separate from the road, but cars do move quickly so care should be taken.

We eventually hopped a fence and slid downhill to join the footpath before it entered a picturesque and snowy woodland. The path followed a small and fast-moving stream and then into the pinewoods before returning to the carpark in Birchin Clough.